With the growing incorporation of the Internet and networks into our lives in all its facets, various kinds of applications have been generated, and with them there are currently multiple types of traffic that demand different bandwidth to circulate through our networks and the Internet . Since we always demand the maximum capacity of our network, especially the Internet connection, it is important to control the use made of this “scarce factor”, to manage it properly according to our needs. For these purposes, various tools that until recently were reserved for corporate environments, are now made accessible as new functionalities of our home routers, so it is interesting to understand in general how they work in order to get the most out of them.

We frequently see a function called QoS, an acronym for Quality of Service or Quality of Service, which refers to various mechanisms designed to ensure the agile flow of data in the network, using mechanisms for assigning priorities to different types of traffic that require more special treatment. We will handle the concept of QoS as differentiated and comprehensive Bandwidth Control, that is, the latter as a part of the Quality of Service.

The purpose of this article is to make a brief description of the main elements of these systems to understand their general operation and that, once we configure our router, we tackle this task in a better position to be able to obtain the best performance that it can give us.

Elements

Scarce factor

The underlying idea behind all these QoS systems is a deficit in the bandwidth necessary to achieve what we want in terms of speed, latency or “jitter” (variations in latency). If this scarcity did not exist (in our network, in our connection or in other networks through which our packets travel) and the bandwidth were unlimited, all types of traffic would obtain more than what they need to achieve their quality and we would not be talking in the way of achieving a better quality of service.

Privileges

Since this deficit cannot be remedied at the moment, we are forced to define different degrees of importance or priority for different types of traffic, so that one type is privileged to the detriment of another. We will always try to minimize this detriment so that it is as less noticeable as possible and if it is very noticeable, that it only affects the types of traffic where it least bothers us.

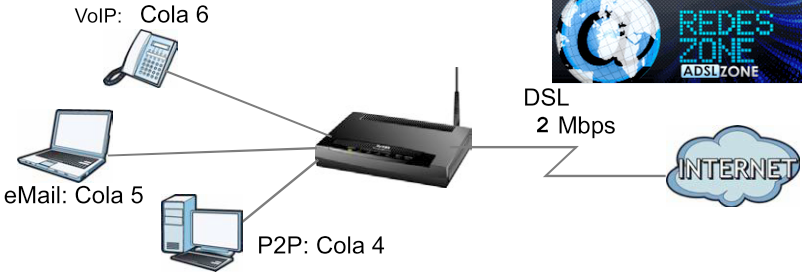

For example, if I am serving a file on a P2P network that consumes a large part of the upload bandwidth of my connection and I have to initiate a call with my IP phone that runs on the same Internet connection, then I pretend that my call will not I have connection problems, even if this means that the file I am uploading takes a little longer than expected. This leads me to decide that my VoIP traffic should have higher privilege than my P2P traffic. Another example: if I am making a large data download to my PC or another on my network, and I need to check the mail, I intend for the mail operation to be fluid even though this slows down the download. Defining which traffic we want to prioritize at the expense of what other is the political definition that we must make and then get down to work with the technical.

Classification

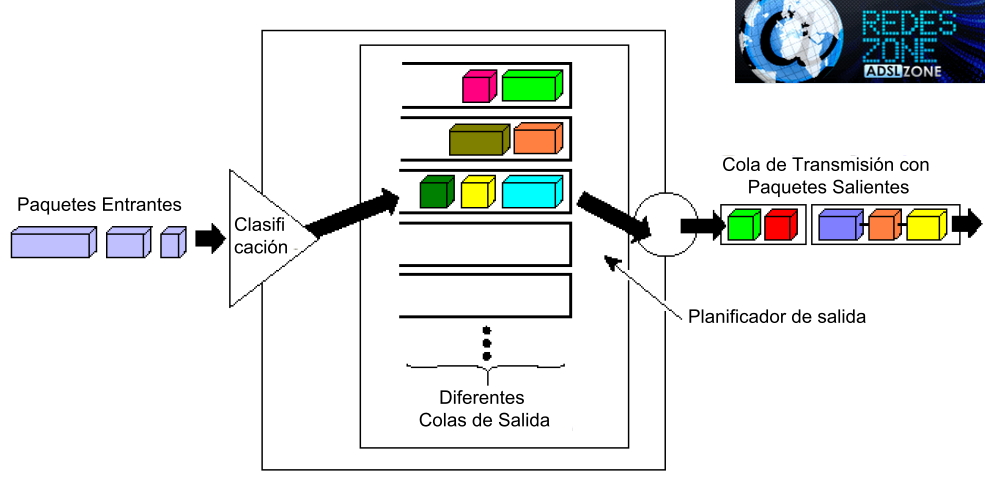

In order to assign privileges or do other types of operations with certain traffic, there must be an unambiguous way to classify it, in the sense of cataloging and identifying it within the entire tangle of traffic that passes through the router. Correctly identifying the traffic we are interested in by the router is a vital operation in order to then be able to have it given or removed priority. All packets that meet certain criteria will be considered as belonging to a certain “Class” of traffic and not to another.

In general, several classes are defined and it is specified what criteria will be used to include each package in one or the other. The number of criteria that can be used to classify and identify traffic is enormous, although it depends on each router. Network traffic is always based on a stream of data packets and classifiers always analyze certain characteristics of these packets individually, classifying them one by one. It is not the purpose of this article to delve into these details, but it is worth mentioning as examples of criteria by which traffic is identified: MAC Address, IP, or port, both source and destination, protocol, packet size, physical mouth per the one that enters the router, SSID (in the case of routers with multiple SSIDs), various marks that the packet brings that may have been assigned by other systems that it has previously passed through, such as VLAN or priority identifiers, etc.

Actions

Once the packet has been classified, the router assigns it the treatment that we have configured for the specific class to which the packet happened to belong. The main action the router performs in order to control bandwidth is to put the packet in one of its output “queues”. Due to the fact that the outgoing bandwidth available to the router to send the packets is limited, what it does is plan the exit, forcing the packets to form different rows or queues to be able to go out, and all of them must go out through the same ” gate ”(the transmission queue of the output interface).

For each Exit Interface (later we will see that only the traffic that “goes out” can be controlled) the router has predefined these different exit queues that it advances at different speeds, sending the packets one by one, using different prioritization schemes for each queue, thus making the different “flows” move at different rates, in a process that aims to assign the scarce bandwidth to the most privileged flows. This process is known as Bandwidth Management, Bandwidth Shapping or Bandwidth Management and they are the main part of Quality of Service systems. In general, the router configuration allows us to choose a “priority” for each class that we define and with that it takes care of putting the packet in the queue that meets our priority.

With the increased processing power that is achieved with the advancement of technology, some routers have added, as an integral part of the QoS process, some other functions in addition to the aforementioned bandwidth management, considering that much of the heavy lifting (which is to classify the packages according to the various criteria) it is done. In this way, it is used to “mark” the packet in different ways that are interpreted by the following networks and devices through which the packet will transit when it leaves the router. We will not delve into the different protocols involved, but it is worth mentioning some common brands such as TOS (Type of Service) and DSCP (Differentiated Services Code Point) in the IP header of the packets, and VLAN brands in the Ethernet header.

The objective of these brands is to establish differentiated priorities in subsequent networks, so that those other devices treat the packet in the same way as our router has done, or to establish special routing conditions. Of course, when our router sends packets to the networks of our ISPs in domestic home connections, they completely ignore these marks and assign them their own priority instead of respecting the one we intend, so these marks end up fulfilling their function only circumscribed. to corporate networks or to devices that we configure ourselves in our own networks.

Router power limit

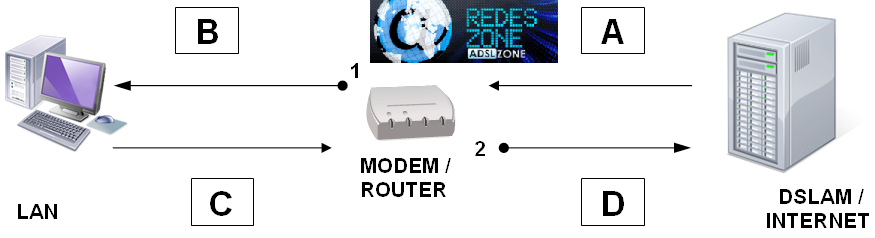

It is very important to note that the router can only act (whatever it is going to do with the packet) on packets it has already received, regardless of whether it received them from the LAN or from the Internet or WAN. Understanding this is important to be able to configure QoS systems because it means that the router can never control the traffic it receives, but rather the traffic it sends, regardless of which interface (WAN or LAN) it receives or which it sends it through. There is an erroneous tendency to assume that the concept of “received” is equivalent to “from the Internet” and that “sent” means “sent to the Internet”, which, from the router’s point of view, is not completely true. To see it graphically, let’s analyze the following scheme. We will assume an ADSL connection, but it is the same for cable, fiber or any technology.

Through points 1 and 2, the router sends traffic on sections B and D, and from the router’s point of view, both are “sent”, being B to our internal network or LAN and D to the Internet or WAN. Segment D is what we commonly know as “Upstream” or Ascent. The traffic that runs through segment A is that which the router “receives” from the Internet, and that which runs through segment C is that which the router “receives” from our LAN.

The router cannot control what happens in A or what happens in C, because it is not it, but another device, who makes the decision to transmit and occupy the bandwidth. The router only has decision-making power at points 1 and 2, controlling the bandwidth used in segments B and D. That is, it can only control what it transmits itself (B for the LAN interface; D for the WAN interface), that is, only the traffic that flows “out” of the router, since these are the only cases where the same router makes the decisions to transmit or not, or to use a certain speed. When we allocate the available bandwidth for each of the interfaces, we are always referring to B or D, never A or C, simply because these last two are segments that are outside the control of the router.

When we try to regulate what we call the DOWNLOAD speed of the PC, where segments A + B are involved, we do so by regulating the throughput at point 1, that is, at the point where the traffic EXITS from the router (the only point where the router is sovereign in that sense of traffic). At that point, according to the criteria set for bandwidth management, the router can, for each packet, decide between FORWARD (send), DELAY (delay) or DROP (discard). You can decide on DELAY if you have free storage capacity for the package, since it must keep it in memory until it is allowed to exit. If you cannot store it, as your ability to retain it is very low, you must decide to DROP (discard).

The problem that arises at this time is that by the time the router can make the decision to discard the packet (because if not, it exceeds the bandwidth assigned to the recipient, and it cannot store it either), the bandwidth that We are interested in optimizing, because of how scarce segment A is (not segment B), it has already been occupied when the DSLAM sent the packet, and if the router discards it, what we will have achieved is that the packet has to to be sent again from the DSLAM, occupying the bandwidth of that critical segment (A). Here we can make a special consideration. If the traffic is TCP type, we know that the recipient must send a confirmation (ACK) to the sender as it receives the shipments, and that if the sender does not receive the confirmation of previously sent packets (because the recipient has not received them already that the router discarded them), then it will send the same packets again (reoccupying the scarce bandwidth with the same information), only that the reception of them by the recipient will have been delayed, but without saving traffic in the critical segment, but quite the opposite.

However, and due to the behavior of the TCP protocol (which has nothing to do with bandwidth management), it may happen that the sender stops sending traffic due to the delay in receiving confirmations. recipient’s reception of previous shipments (this depends on many factors, including the RWIN value of the TCP protocol), causing an interruption in the flow of data before resending the unconfirmed data. This small delay in forwarding the traffic will generate a certain space or bandwidth available for other traffic, and constitutes an INDIRECT way of achieving a certain effect in segment A by operating on segment B, but it is a very unreliable way, inefficient and very expensive in terms of bandwidth, since packets that had already been sent and consumed bandwidth at the time, have been discarded by the router and must now be sent again, consuming bandwidth again. In short, the recipient receives the most time-spaced information on segment B, but at the expense of multiplying the total traffic on segment A, creating the illusion that their bandwidth has been optimized.

In the case of traffic that is not transported with the TCP protocol, but mainly with UDP, the concept of “indirect handling” mentioned in the previous paragraph does not apply, since the UDP protocol is more rudimentary and does not have the recovery characteristics mentioned. It is important to mention that several important streaming protocols are transported based on UDP, which implies that improper bandwidth management can cause deficiencies in streaming as well as saving absolutely nothing in bandwidth consumption.

When it comes to regulating the UPLOAD, that is, the upload from the PC to the Internet, it is when the router’s bandwidth management mechanism is most efficient, since all the concepts mentioned for the download traffic are applicable to the traffic of rise. In this case, the critical segment for us is D, which can be easily controlled by the router due to the sovereignty it has at point 2, since at that point, everything depends on it and not on third parties. On the other hand, the asymmetry characteristic of our domestic connections means that segment D always has much less bandwidth than all the others, so it is particularly important to use the available bandwidth correctly. This is so to the point that a large number of QoS systems in home routers only contemplate the management of this segment. Here it is particularly important to remember the bidirectional operation of the TCP protocol, which also makes important use of the upstream channel even if only one download is being performed. Unlike the downstream traffic model, in this case we do not care that the regulation of the bandwidth of segment D is done with extra cost for segment C, since the latter has a much higher bandwidth than D and we can afford that “waste.”

Here it would be necessary to represent the wireless WLAN interface, which WiFi routers incorporate as a third physical interface and has its own bandwidth, but it is worth mentioning that it behaves exactly the same as the LAN and the WAN in terms of what traffic is the that is controlled, that is, the one that GOES OUT from the router via WiFi.

In summary, in order to design an efficient QoS scheme, we must assimilate the concept that the router can only control the traffic that it sends itself, that is, the one that EXITS the router through any of its interfaces, not the one that receives or enters from from other sides.

conclusion

Due to the scarce factor that turns out to be the available bandwidth in various conditions, the QoS systems that modern routers incorporate have been devised to be able to alleviate this scarcity in some way. These systems require the definition of privileges to be assigned to different types of traffic. To be able to assign these differentiated privileges, the router must classify the traffic packets into different categories or classes to which it will grant different bandwidth and mark differently only at the moment those packets leave the router.