Fiber optic links are already the primary method of transferring data between groups of servers in data centers, and engineers want to bring their incredible bandwidth to the realm of processors . This step has a high cost but the key is in what they have dubbed Plasmonics (plasmonics) , a method by which several CPUs could be linked using light but without the need for fiber optics.

Silicon photonic components are huge compared to their electronic counterparts, and that for now prevents their use in processors that, as you know, work with transistors with dimensions of nanometers. This creates considerable additional difficulty and costs, but researchers at the University of Toronto in the US and at ARM itself believe that they can greatly reduce these problems.

Plasmonics, or how to link CPUs using light beams

That silicon photonic components are much larger than electronic ones is not because the technique does not allow them to be made smaller, but because it is a function of the optical wavelengths, which are much larger than current transistors and copper interconnects. that link the circuits. The photonic components of silicon are also too sensitive to changes in temperature, so much so that the chips must include heating elements that occupy about half their area and power consumption.

In a virtual conference, a researcher from the Amr S. Helmy lab described new silicon transceiver components that circumvent both problems by relying on Plasmonics rather than photonics. The results point to transceivers capable of doubling (at least) the bandwidth while consuming a third and occupying 20% of the area; what’s more, they could be built directly on top of the processor rather than on separate chiplets as is done with silicon photonics.

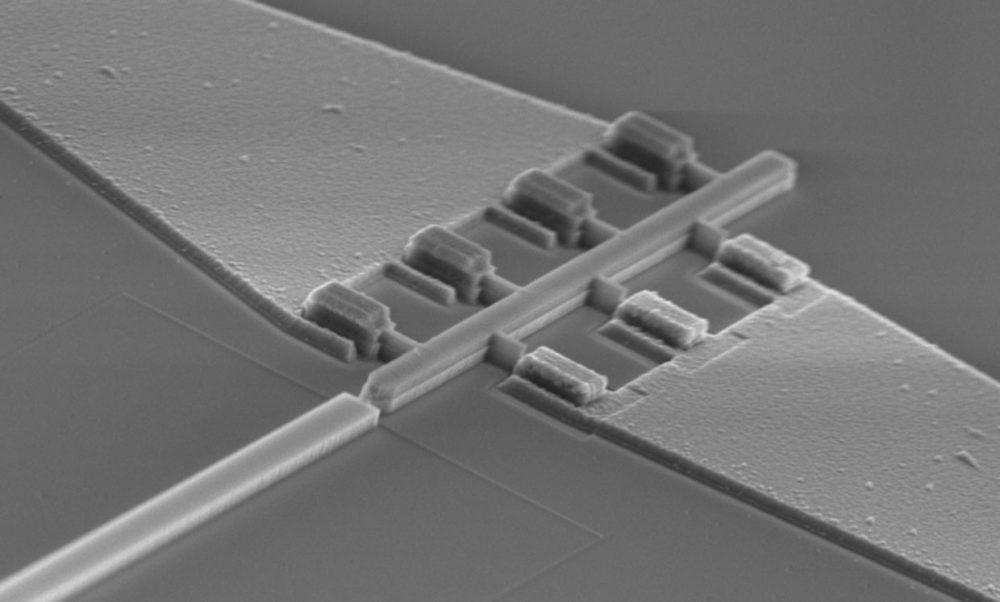

When light hits the interface between a metal and an insulator at a shallow angle, plasmons are formed: waves of electron density that propagate along the surface of the metal. Conveniently, plasmons can travel down a waveguide that is much narrower than the light that forms it, but they usually turn off very quickly because the metal absorbs the light.

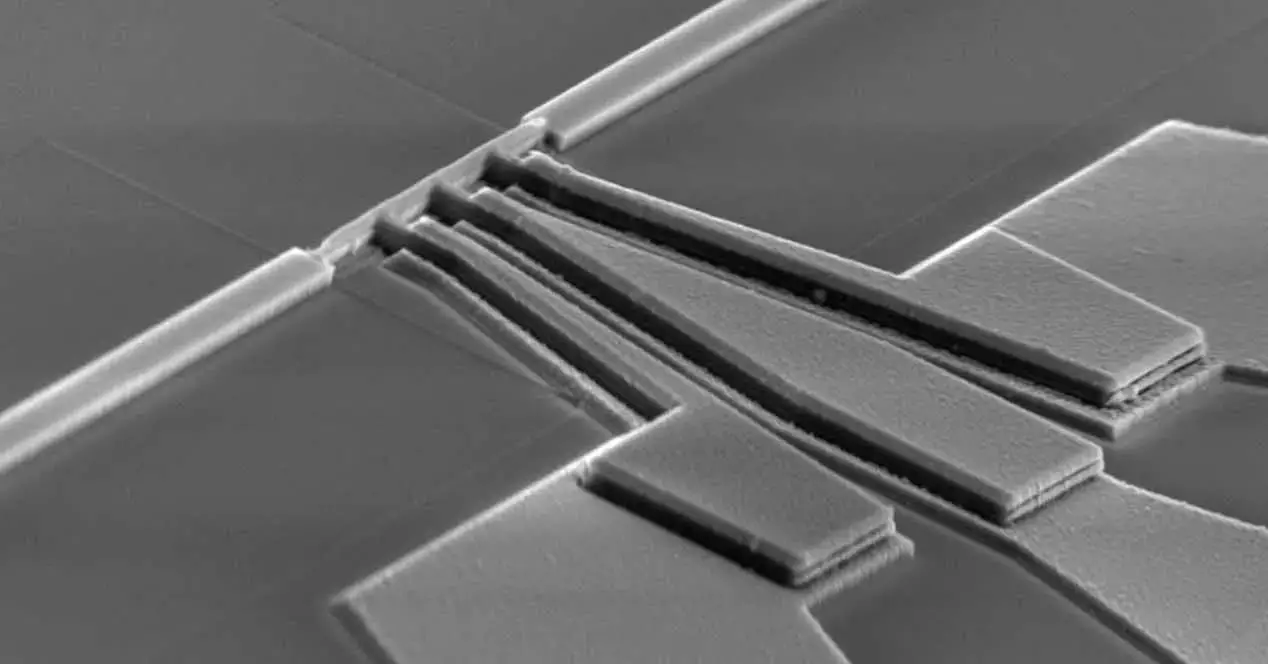

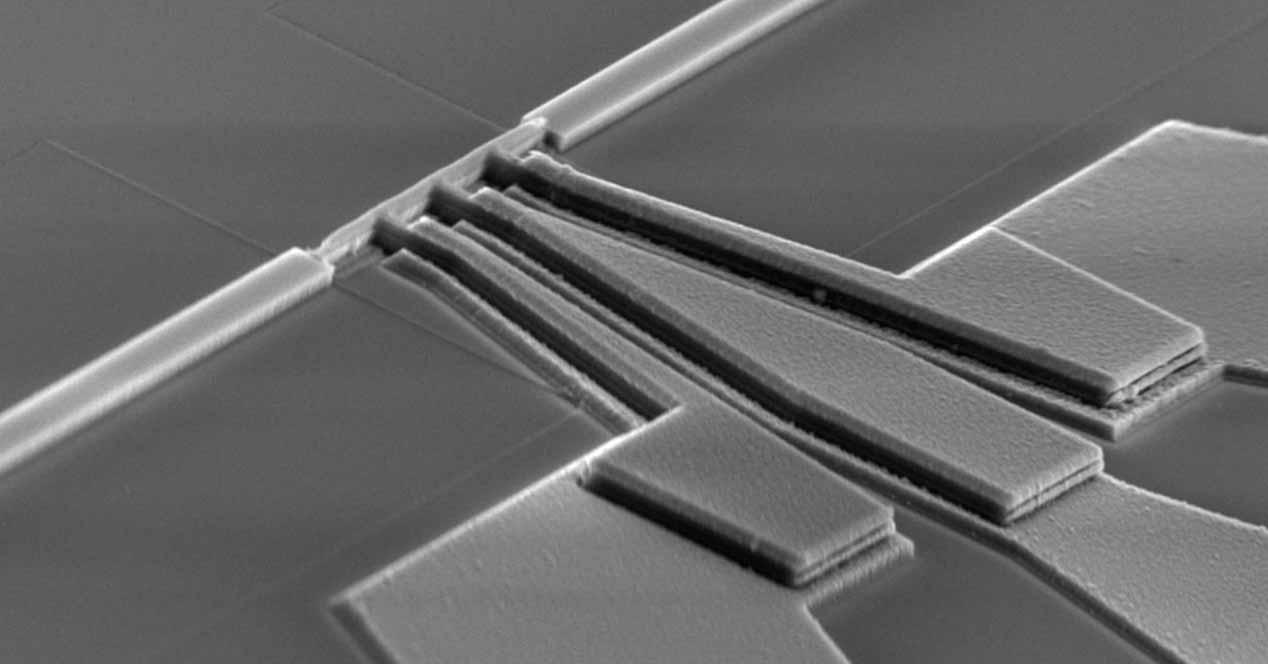

Thus, the Toronto researchers have invented a structure to take advantage of the smaller size of plasmonics and, at the same time, greatly reduce energy loss. Called a coupled-hybrid plasmon waveguide (CPHW), it essentially consists of a stack made up of silicon, indium, tin oxide, silicon dioxide, aluminum, and more silicon. This combination forms two types of semiconductor junctions, a Schottky diode and a metal oxide semiconductor, with the aluminum containing the plasmon in common between the two. Within the metal, the plasmon at the upper junction interferes with that at the lower junction in such a way that the loss is reduced by almost two orders of magnitude.

Using CPHW as a base, two key photonic components are built: a modulator that converts electronic bits to photonic and a photodetector, which does the opposite. The modulator occupies only 2 square micrometers and can switch between states at a frequency of 26 GHz, the limit of the equipment available to researchers, but according to the measured capacitance the theoretical limit would be no less than 636 GHz.

What would this technology do?

Linking multiple CPUs has huge computational benefits; Imagine that we can literally have two processors running simultaneously in the system, without interfaces that limit their bandwidth. Currently it is possible to transmit up to 39 Gbps, but this technology would allow to transmit comfortably and without having to resort to error correction at 150 Gbps, so we would be talking about more than four times more bits per second and all integrated in the same package , without having to resort to chiplet technology.

In short, linking several CPUs in this way would allow us to significantly increase the performance that a processor can give us today, and what is more, it would allow to integrate processors within processors almost literally, multiplying the gross performance by two.