Although we have previously talked about certain problems that will keep Intel and AMD sleepless for years, it is also true that we have done it quite generally when we have referred to nanometers themselves. In this regard, and although AMD is a spectator, everything is focused on the fight between Intel and TSMC, which are going to have to implement major changes in the interconnection if they want to drop nanometers. What problems are they currently having?

Everything seems easy and wonderful, technology advances, new products arrive faster at the same price or slightly above and we all rejoice in fights between companies to see who gets our money.

But from the backstage , there are hundreds of engineers for each company that are doing their best to keep this industry afloat, because remember, if you don’t manage to drop nanometers, in a few years performance would stagnate and both AMD and Intel NVIDIA would have to focus all their efforts on techniques such as vertical stacking.

Even so, the limit would be reached very quickly and we would return to the initial problem. Therefore, the industry is dominated by the best node and the best architecture, the problem is that from now on, the paradigms in the wafers have to change.

The interconnection between wafers, a new bottleneck of difficult solution

As we well know, the layers of the wafers together with their masks are a problem that the whole industry tries to solve, especially facing EUV as a new form of engraving. But as the transistors get smaller and smaller, as the chips get bigger and, above all, they manage to work more information per second, the way to create those same chips begins to reach its limit.

The 7nm pre-EUV will be the last to maintain the typical initial material structure for TSMC. In Intel it is represented by 14 nm ++ and in Samsung it will also be its 7 nm without EUV that will keep the rules of the game intact.

The interconnecting layers of the wafers are suffering serious problems in the following lithographic processes, especially between the so-called M0 and M1 . Reducing the nanometer scale will from now on imply coatings between thinner layers, thinner barriers and metals with lower resistances to guarantee the structure of said wafers.

Current wafers use ultrapure copper for such interconnects, but although copper has been with us for more than 10 years (130nm), it is not stable from the nanometers previously discussed and engineers are looking for a substitute that has its properties and minimizes their defects.

The first to move tab has been Intel, its 10 nm include in its first two layers (the most delicate in terms of structure and interconnections) a material as well known as cobalt, where said material is used in coatings and bonds. Curiously, the rest of the layers use copper again due to its lower cost and stability, especially in higher layers.

Why has copper become a solution to a problem?

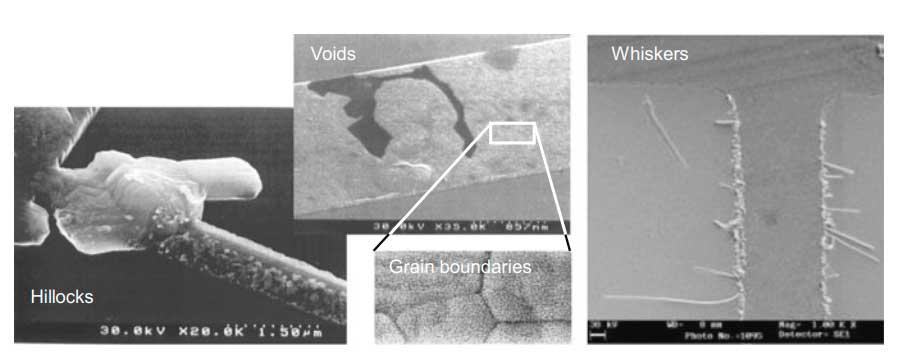

Due to the properties of the material itself, copper as the nanometer reductions advance has a counterproductive effect on the interconnects of the wafers: it diffuses with the surrounding materials.

What has been done to avoid this effect is to cover it with a layer as a barrier that due to the named reductions has become so thin that it is not viable. We are talking about 1 or 2 nm thick layers for this material, something that does not solve the copper problem, it only alleviates it and when a manufacturer faces a new reduction, perfection is synonymous with viability for said node.

A lack of only a few atoms and the effect of the barriers disappears, damaging the structure and performance of the wafer, which is why, as we see, the precision is of such caliber that it ceases to be a method to be followed and we must look for other ways they do not require such a large expense and it has so little future. To this we must add thermal cycles, copper is highly dependent on them and electromigration takes its toll.

Electromigration, a fundamental effect to cancel defects

The new materials that are under development seek not only to replace copper as such, but to improve as regards the migration of atoms. The limitation in this section is key, since they prevent a wafer from contaminating between layers.

Two poorly insulated layers can undoubtedly spoil not only the affected wafer, but thousands or millions since the effect will be replicated in each and every one of them. Therefore, the process of creating the structure is increasingly complex and perfect.

Due to this, two materials are being used in the development of lithographic processes such as the 5 nm from Intel or the 3 nm from TSMC / AMD: cobalt and ruthenium. The main strengths of these two are that they limit any type of migration where they can act as a barrier or as a conductor.

Cobalt is not new to the industry as such, but ruthenium is not the biggest challenge for engineers. The problem is that manufacturers as such are very reluctant and we could almost call them conservative when it comes to making changes, which is leading the industry to become less and less profitable in the price of wafers.

The fight will turn between necessity and that conservatism that can define the lithographic processes of the future. Therefore, the industry in general needs a material that does not need coatings and can comply with everything that copper did, that is, have all its virtues and no defects.

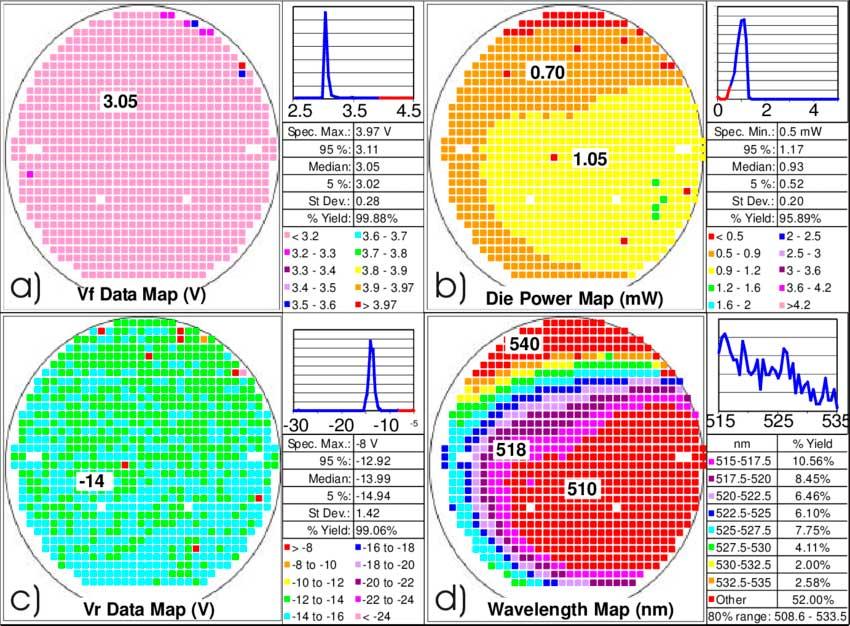

Costs are and will be a problem, there could be a segmentation in the wafers

The industry as reluctant to implement changes that has swallowed billions in previous investment is not going to stop thinking about the final costs at which you can sell a wafer. Therefore, and although they will have to yield to maintain the advance, it is speculated that it could be the case that two or more types of wafers were attributed to the same node.

The first and cheapest would try to be the one that uses common materials and patterns and has less innovation. The second could be the one that, with a higher price, implements the best materials and the latest interconnection techniques, even managing to reduce nanometers even more than its sister wafer.

We are seeing something like this today with Samsung and its 7nm and 8nm respectively, where Koreans are able to improve the density thanks to certain compounds and various minor optimizations. Logically they offer two different prices for each type of wafer, so in the future we could not only see LP, LPP with different types of transistors, but wafers with different densities that are manufactured in the same way with little difference, segmentation they call it.

Transistors shrink, but patch cables go slower, when will they be a problem?

The so-called “interconnect cables” will also face another problem and is only their size. Transistors shrink, but transistors remain more or less stable and will pose a problem in not too long.

The most advanced so far apparently and according to various studies that are being published are around 12 nm , with the tonic being 18 nm for each of them. This multiplied by millions of cables represents a total area too large for 3nm lithographic processes.

Gaining density and thus space to house more transistors per mm2 can be hindered if interconnect cables do not improve in size and scale similarly to these. Although there are some significant advances in this regard, there is far from a consensus and defining evidence that shows a real improvement in this section.

Therefore, it is another aspect that the industry has to solve at the same time as the materials, let’s just hope that the price per wafer does not increase and that if possible it ends up falling so that the final prices at least do not increase.